Embark on an exciting journey into the world of web game development with our comprehensive guide on how to coding game with javascript canvas. This exploration will illuminate the foundational concepts of the HTML5 Canvas element, unveiling its core drawing APIs and common applications in creating dynamic, interactive web experiences. Discover the distinct advantages Canvas offers for crafting engaging 2D games, setting the stage for your creative endeavors.

We will meticulously guide you through setting up your development environment, from creating basic HTML structures to acquiring the rendering context and defining Canvas dimensions. The process of drawing fundamental game elements, including shapes, text, and static assets, will be demystified, providing you with the essential building blocks for your game’s visual presentation.

Introduction to JavaScript Canvas for Game Development

Embarking on game development within a web browser environment opens up a world of creative possibilities, and at the heart of many dynamic and interactive web experiences lies the HTML5 Canvas element. This powerful feature provides a flexible drawing surface that developers can manipulate using JavaScript to render graphics, animations, and ultimately, engaging games. Understanding its fundamentals is the crucial first step for any aspiring web game developer.The HTML5 Canvas element, represented by the ` ` tag in HTML, acts as a blank slate on a webpage. It doesn’t render anything on its own; instead, it serves as a container for graphics that are drawn onto it using a JavaScript API. This API provides a rich set of tools and methods to create shapes, draw lines, render text, manipulate images, and even apply transformations like rotation and scaling.

Core Drawing APIs in JavaScript Canvas

The JavaScript Canvas API offers a comprehensive set of functionalities for drawing and manipulating graphical elements. These APIs are accessed through a rendering context, most commonly the 2D rendering context, obtained via the `getContext(‘2d’)` method of the canvas element. This context provides access to various drawing methods.Here are some of the fundamental drawing APIs available:

- Paths: These are sequences of points that define shapes. You can start a new path with `beginPath()`, move to a starting point with `moveTo(x, y)`, add lines with `lineTo(x, y)`, draw arcs with `arc(x, y, radius, startAngle, endAngle)`, and close the path with `closePath()`.

- Shapes: Basic shapes can be drawn directly or by stroking and filling paths. For example, `rect(x, y, width, height)` draws a rectangle, and `fill()` or `stroke()` methods are used to render the defined path.

- Colors and Styles: You can set the color for drawing lines and shapes using `strokeStyle` and `fillStyle` properties, respectively. These properties accept color values like hex codes, RGB, or named colors. Gradients and patterns can also be applied for more complex styling.

- Text: The Canvas API allows you to render text with methods like `fillText(text, x, y)` to draw filled text and `strokeText(text, x, y)` to draw Artikeld text. You can control font properties, alignment, and baseline using properties like `font`, `textAlign`, and `textBaseline`.

- Images: Images can be drawn onto the canvas using the `drawImage()` method. This method is versatile and can draw an image as is, or a portion of an image, and can also be used to scale images.

- Transformations: The canvas context supports transformations that affect subsequent drawing operations. These include `translate(x, y)` to move the origin, `rotate(angle)` to rotate the coordinate system, and `scale(x, y)` to scale the coordinate system.

- Pixel Manipulation: For advanced graphics, you can access and manipulate individual pixels on the canvas using methods like `getImageData(x, y, width, height)` to retrieve pixel data and `putImageData(imageData, x, y)` to draw it back.

Common Use Cases of Canvas in Interactive Web Experiences

The versatility of the Canvas API makes it a cornerstone for a wide array of interactive web applications beyond just games. Its ability to dynamically render graphics and respond to user input allows for rich and engaging user interfaces and data visualizations.Some common use cases include:

- Data Visualization: Creating dynamic charts, graphs, and maps that update in real-time based on data feeds. Libraries like D3.js often leverage Canvas for performance when rendering large datasets.

- Image Editing and Manipulation: Developing web-based image editors that allow users to apply filters, crop, resize, and make other modifications to images directly in the browser.

- Interactive Infographics: Building visually appealing and interactive infographics that guide users through complex information with animations and clickable elements.

- Real-time Drawing and Collaboration Tools: Applications like online whiteboards or collaborative design tools that allow multiple users to draw and annotate on a shared canvas simultaneously.

- User Interface Components: Crafting custom UI elements that go beyond standard HTML elements, such as custom sliders, progress bars, or animated buttons.

Advantages of Using Canvas for 2D Game Creation

When it comes to developing 2D games for the web, the HTML5 Canvas element offers several compelling advantages that make it a preferred choice for many developers. Its performance characteristics and direct control over rendering are particularly beneficial for game development workflows.The primary advantages include:

- Performance: Canvas rendering is generally very performant, especially for complex scenes with many objects. Because it’s a pixel-based drawing surface, it can be highly optimized for drawing and updating graphics quickly, which is essential for smooth game animations and responsiveness.

- Direct Control: Developers have fine-grained control over every pixel and element drawn on the canvas. This level of control is crucial for implementing custom game mechanics, physics, and unique visual effects that might not be achievable with other web technologies.

- Cross-Browser Compatibility: The HTML5 Canvas API is widely supported across modern web browsers, ensuring that games developed with it can reach a broad audience without significant compatibility issues.

- Flexibility: The Canvas API is highly flexible. It allows for the creation of virtually any 2D graphic imaginable, from simple sprites to complex particle systems. This flexibility is key for realizing diverse game art styles and mechanics.

- Resource Efficiency: Compared to DOM manipulation for graphics, Canvas can be more resource-efficient, particularly when dealing with a large number of moving elements. Instead of creating and updating numerous DOM nodes, the canvas draws directly to a bitmap.

- Integration with Other Web Technologies: Canvas integrates seamlessly with other HTML5 features and JavaScript libraries. This allows for the incorporation of sound, network communication, and user input handling to create complete game experiences.

Setting Up the Canvas Environment

Welcome back! Now that we have a foundational understanding of JavaScript Canvas, it’s time to get our hands dirty and set up the environment for our game. This involves creating the necessary HTML structure and linking it with our JavaScript code to prepare the canvas for drawing and interaction.This section will guide you through the essential steps to establish a functional canvas element within an HTML document and how to access its drawing capabilities using JavaScript.

We will cover creating the HTML file, obtaining the rendering context, defining the canvas size, and basic styling, laying the groundwork for all subsequent game development activities.

Creating the Basic HTML File with a Canvas Element

To begin, we need a simple HTML file that includes the ` ` element. This element acts as the drawing surface for our game. You can create this file using any text editor.Here’s a minimal HTML structure:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<title>JavaScript Canvas Game</title>

<style>

canvas

border: 1px solid black; /* For visibility during development

-/

</style>

</head>

<body>

<canvas id="gameCanvas" width="800" height="600"></canvas>

<script src="game.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

In this structure:

- The `<canvas>` tag is essential. We give it an `id` attribute (“gameCanvas”) so we can easily reference it in JavaScript.

- The `width` and `height` attributes define the dimensions of the canvas in pixels.

- A basic CSS style is included to add a border, making the canvas visible on the page during development.

- The `<script src=”game.js”></script>` tag links our HTML to a separate JavaScript file named “game.js”, where all our game logic will reside.

Obtaining the Canvas Rendering Context

Once the HTML is set up, the next crucial step is to get access to the drawing API provided by the canvas element. This is done by obtaining its “rendering context.” For 2D graphics, we’ll use the `2d` context.

In your `game.js` file, you will first need to select the canvas element from the DOM and then request its 2D rendering context.

Here’s how you do it in JavaScript:

const canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

The `document.getElementById(‘gameCanvas’)` line retrieves the canvas element using its ID. The `canvas.getContext(‘2d’)` method then returns an object that provides methods and properties for drawing 2D graphics on the canvas. If the browser doesn’t support the canvas, `getContext` will return `null`. It’s good practice to check for this.

Setting the Canvas Dimensions and Styling

While we set the initial dimensions of the canvas using the `width` and `height` attributes in HTML, these can also be set or modified programmatically via JavaScript. Furthermore, you can apply various CSS styles to the canvas element itself, such as background colors, margins, and positioning, to integrate it seamlessly into your web page layout.

You can set the dimensions and apply styles like this:

const canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

// Setting dimensions programmatically

canvas.width = 800;

canvas.height = 600;

// Applying styles via JavaScript

canvas.style.backgroundColor = '#f0f0f0';

canvas.style.display = 'block'; // To remove extra space below canvas

canvas.style.margin = '20px auto'; // Center the canvas

canvas.style.border = '2px solid blue';

It’s important to note that setting `canvas.width` and `canvas.height` in JavaScript not only changes the displayed size but also clears the canvas and resets its internal coordinate system.

This is different from CSS styling, which only affects the element’s appearance and scaling. For games, it’s generally recommended to set dimensions using the HTML attributes or JavaScript properties for precise control over the drawing surface.

Designing a Simple Code Structure for Initializing Game Elements

A well-organized code structure is vital for managing the complexity of a game. For initialization, it’s common to have a main function that sets up the game state, loads any necessary assets, and then begins the game loop.

A typical initialization structure in `game.js` might look like this:

let canvas;

let ctx;

function init()

canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

// Set canvas dimensions and basic styling

canvas.width = 800;

canvas.height = 600;

canvas.style.border = '1px solid black';

// Initialize game elements here

// For example, creating player object, enemy objects, etc.

console.log("Canvas initialized and ready for drawing!");

// Start the game loop (which we'll cover later)

// gameLoop();

// Call the init function when the DOM is ready

window.onload = init;

// Or using DOMContentLoaded for potentially faster execution

// document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', init);

In this structure:

- Global variables `canvas` and `ctx` are declared to hold references to the canvas element and its context, making them accessible throughout the script.

- The `init()` function encapsulates all the setup logic.

- Inside `init()`, we obtain the canvas and context, set dimensions, and apply basic styling.

- A placeholder comment indicates where you would typically create and initialize your game entities (like player characters, enemies, UI elements, etc.).

- The `window.onload` event listener ensures that the `init()` function is called only after the entire page, including all resources like images, has finished loading. `DOMContentLoaded` is often preferred as it fires when the HTML document has been completely loaded and parsed, without waiting for stylesheets, images, and subframes to finish loading.

Drawing Basic Game Elements

Now that we have our canvas set up and ready, the next crucial step in game development is learning how to draw the fundamental elements that will populate our game world. This includes everything from static backgrounds and platforms to interactive player characters and enemy sprites. Mastering these drawing techniques will lay the groundwork for creating visually engaging and functional games.

The HTML5 Canvas API provides a rich set of methods for drawing various shapes, applying colors and styles, and rendering text. We’ll explore these capabilities to bring our game’s visual components to life.

Drawing Shapes

The Canvas API offers straightforward methods for drawing common geometric shapes. These shapes form the building blocks of many game assets.

- Rectangles: Rectangles are frequently used for platforms, UI elements, and even character hitboxes. The primary methods are:

fillRect(x, y, width, height): Draws a filled rectangle.strokeRect(x, y, width, height): Draws a rectangle with an Artikel.clearRect(x, y, width, height): Clears a rectangular area on the canvas, making it transparent.

The `x` and `y` coordinates specify the top-left corner of the rectangle, while `width` and `height` define its dimensions.

- Circles: Circles, or arcs, are essential for projectiles, power-ups, and rounded game elements. Drawing circles requires using the `arc()` method.

arc(x, y, radius, startAngle, endAngle, anticlockwise)Here, `x` and `y` are the center coordinates of the circle, `radius` is its size, `startAngle` and `endAngle` define the arc’s sweep in radians, and `anticlockwise` is a boolean indicating the direction of the arc. To draw a full circle, `startAngle` is typically 0 and `endAngle` is 2

– Math.PI. - Lines: Lines are used for drawing paths, borders, or simple visual effects. The process involves defining the path and then drawing it.

- Begin a path with

beginPath(). - Move the drawing cursor to the starting point using

moveTo(x, y). - Draw a line to a new point using

lineTo(x, y). - Finally, render the line using

stroke().

- Begin a path with

Applying Colors and Strokes

To make our shapes visually distinct and appealing, we can control their fill and Artikel colors. The Canvas API uses properties of the 2D rendering context for this.

- Fill Color: The

fillStyleproperty sets the color used to fill shapes. It accepts color values like named colors (e.g., “red”), hexadecimal codes (e.g., “#FF0000”), or RGB/RGBA values (e.g., “rgb(255, 0, 0)” or “rgba(255, 0, 0, 0.5)”). After settingfillStyle, any subsequent filled shape will use this color. - Stroke Color: Similarly, the

strokeStyleproperty defines the color of the Artikel for shapes. It accepts the same color formats asfillStyle. - Line Width: The

lineWidthproperty controls the thickness of lines and strokes. A value of `1` is the default. - Drawing Process: For any shape, you typically set the desired fill and/or stroke styles, then call the appropriate drawing method (e.g., `fillRect()`, `arc()`, `stroke()`).

Drawing Text

Text is essential for displaying scores, messages, instructions, and character names in games. The Canvas API provides methods for rendering text with various styling options.

- Rendering Text:

fillText(text, x, y): Draws a solid text string at the specified coordinates.strokeText(text, x, y): Draws an Artikeld text string.

The `x` and `y` coordinates define the anchor point of the text, which can be influenced by alignment properties.

- Text Styling:

font: This property sets the font family, size, and weight, similar to CSS (e.g., `”30px Arial”` or `”bold 16px sans-serif”`).textAlign: Controls the horizontal alignment of the text relative to the `x` coordinate. Possible values include `”left”`, `”right”`, `”center”`, `”start”`, and `”end”`.textBaseline: Controls the vertical alignment of the text relative to the `y` coordinate. Possible values include `”top”`, `”bottom”`, `”middle”`, `”alphabetic”`, and `”hanging”`.

It’s important to set these styling properties before calling `fillText()` or `strokeText()`.

Drawing Static Game Assets

With the fundamental drawing methods at our disposal, we can now create static elements that form the visual foundation of our game. These assets, once drawn, typically remain in place unless the game logic dictates otherwise.

Example: Drawing Platforms

Platforms are common in many game genres, providing surfaces for the player to stand on. We can draw them as simple filled rectangles.

Imagine a game where platforms are colored brown. We would first set the fillStyle to a brown color, then use fillRect() to draw each platform at its desired position and size.

For instance, to draw a platform starting at coordinates (50, 400) with a width of 200 pixels and a height of 20 pixels, and a brown fill:

// Assuming 'ctx' is our 2D rendering context

ctx.fillStyle = "#8B4513"; // A shade of brown

ctx.fillRect(50, 400, 200, 20);

Example: Drawing a Player Sprite Placeholder

While complex sprites are often loaded from images, we can use basic shapes to represent a player character during development. A simple circle or rectangle can serve as a placeholder.

If our player is represented by a blue circle, we would set the fillStyle to blue and use the `arc()` method.

To draw a player circle centered at (100, 300) with a radius of 25 pixels:

ctx.fillStyle = "blue";

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.arc(100, 300, 25, 0, Math.PI

- 2); // Full circle

ctx.fill();

These examples demonstrate how to combine basic shape drawing with color and styling to create the visual components of your game. As you progress, you will learn to combine these elements and animate them to create dynamic gameplay.

Animation and Game Loops

Welcome back! Now that we’ve established the fundamentals of setting up our canvas and drawing basic elements, it’s time to bring our game to life with animation. This is where the magic truly happens, transforming static drawings into dynamic experiences. We’ll explore the core concept of a game loop, which is the heartbeat of any interactive application, and learn how to implement it efficiently using JavaScript.A game loop is a continuous cycle that handles everything from rendering graphics to processing user input and updating game logic.

It’s responsible for drawing each frame of your game, ensuring that the visuals are smooth and responsive. Without a well-structured game loop, your game would appear frozen or jerky.

The Game Loop Concept

The game loop is a fundamental pattern in game development. It’s an infinite loop that repeatedly performs three main tasks: processing input, updating game state, and rendering the game to the screen. This constant cycle allows the game to feel alive and interactive.A typical game loop structure can be visualized as follows:

while (gameIsRunning) processInput(); updateGame(); renderGame();

This conceptual loop highlights the sequential nature of game updates and rendering. In practice, we achieve this with modern browser APIs.

Implementing Smooth Animations with `requestAnimationFrame`

For creating smooth and efficient animations in web browsers, `requestAnimationFrame` is the standard and recommended method. It’s a special function provided by the browser that tells the browser you wish to perform an animation and requests that the browser calls a specified function to update an animation before the next repaint. This is significantly more performant and battery-efficient than using `setInterval` or `setTimeout` for animations.

Here’s how you can implement `requestAnimationFrame` to create a basic animation loop:

let animationFrameId;

function gameLoop()

// Update game logic and state here

update();

// Render the game

render();

// Request the next frame

animationFrameId = requestAnimationFrame(gameLoop);

function update()

// Your game logic for updating positions, scores, etc.

console.log("Updating game state...");

function render()

// Your drawing logic to update the canvas

console.log("Rendering game frame...");

// Start the game loop

gameLoop();

// To stop the loop (e.g., when the user navigates away)

// cancelAnimationFrame(animationFrameId);

The `requestAnimationFrame` function ensures that your `gameLoop` function is called just before the browser is about to perform its next screen repaint.

This synchronization with the browser’s rendering cycle results in fluid animations and avoids unnecessary work when the tab is inactive.

Clearing the Canvas Between Frames

A crucial aspect of animation is ensuring that each new frame is drawn on a clean slate. If you don’t clear the canvas after drawing each frame, you’ll end up with trails of previous drawings, creating visual artifacts. This is because the canvas is a bitmap, and new drawings are simply added on top of existing pixels.

To clear the entire canvas, you can use the `clearRect()` method of the 2D rendering context. This method takes four arguments: the x-coordinate of the top-left corner of the rectangle to clear, the y-coordinate of the top-left corner, the width of the rectangle, and the height of the rectangle. To clear the entire canvas, you’ll use the canvas’s full width and height.

Here’s how you integrate clearing into your `render` function:

const canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

function render()

// Clear the entire canvas

ctx.clearRect(0, 0, canvas.width, canvas.height);

// Draw your game elements here

ctx.fillStyle = 'blue';

ctx.fillRect(50, 50, 100, 100); // Example drawing

By calling `ctx.clearRect(0, 0, canvas.width, canvas.height)` at the beginning of your `render` function, you ensure that each frame starts fresh, preventing any lingering graphics from previous frames.

Updating Game Object Properties

Within the `update` function of your game loop, you’ll manage the logic for how your game elements change over time. This includes moving characters, updating scores, checking for collisions, and any other dynamic aspects of your game. Game objects are typically represented by JavaScript objects that hold their state (position, velocity, health, etc.) and can have methods to update their state.

Let’s consider a simple game object, like a player-controlled square that moves across the screen.

First, define a player object:

let player = x: 50, y: 100, width: 30, height: 30, color: 'red', dx: 2, // Horizontal velocity dy: 0 // Vertical velocity ;

Now, modify the `update` function to change the player’s position:

function update()

// Update player position

player.x += player.dx;

player.y += player.dy;

// Basic boundary checking to keep player on screen (example)

if (player.x + player.width > canvas.width || player.x canvas.height || player.y < 0)

player.dy = -player.dy; // Reverse direction

console.log(`Player position: x=$player.x, y=$player.y`);

And update the `render` function to draw this player object:

function render() ctx.clearRect(0, 0, canvas.width, canvas.height); // Draw player ctx.fillStyle = player.color; ctx.fillRect(player.x, player.y, player.width, player.height);

By updating the `x` and `y` properties of the `player` object within the `update` function and then using these updated properties to draw the player in the `render` function, you achieve animation. The game loop ensures this process repeats continuously, creating the illusion of movement.

Handling User Input

Engaging gameplay relies heavily on responsive controls, allowing players to interact with the game world. In JavaScript canvas game development, this means effectively capturing and processing input from various devices, primarily the keyboard and mouse. By understanding how to listen for and interpret these events, you can translate player actions into meaningful in-game commands, bringing your game to life.

This section will guide you through the essential techniques for capturing keyboard and mouse input, and then demonstrate how to integrate this handling logic seamlessly into your game loop for a smooth and interactive experience.

Keyboard Event Capture

Player movement, actions, and menu navigation are commonly controlled via the keyboard. JavaScript provides built-in event listeners to detect when a key is pressed or released. These events are crucial for implementing responsive character movement and activating abilities.

The two primary keyboard events to utilize are `keydown` and `keyup`.

- The `keydown` event fires when a key is pressed down. This is often used to initiate an action, such as moving a character in a specific direction.

- The `keyup` event fires when a key is released. This is typically used to stop an action, like ceasing movement when the player lets go of a directional key.

You can attach event listeners to the `document` object to capture these events globally. The event object passed to the listener contains valuable information, such as the `key` property, which identifies which key was pressed (e.g., ‘ArrowUp’, ‘w’, ‘Space’).

Here’s a basic example of how to set up keyboard event listeners:

document.addEventListener('keydown', (event) =>

// Handle key press

console.log(`Key pressed: $event.key`);

);

document.addEventListener('keyup', (event) =>

// Handle key release

console.log(`Key released: $event.key`);

);

Mouse Event Capture

For games that require precise aiming, clicking on objects, or interacting with menus via a pointer, mouse input is indispensable. JavaScript offers a suite of events to track mouse activity, including clicks, movements, and button states.

The most common mouse events include:

- `click`: Fires when the mouse button is clicked.

- `mousedown`: Fires when a mouse button is pressed down.

- `mouseup`: Fires when a mouse button is released.

- `mousemove`: Fires when the mouse pointer moves over the canvas.

When handling mouse events on the canvas, it’s important to consider the canvas’s position and dimensions on the page to accurately calculate the mouse coordinates relative to the canvas itself. The `event.clientX` and `event.clientY` properties provide the mouse coordinates relative to the viewport, which can then be adjusted using the canvas’s `getBoundingClientRect()` method.

The `mousemove` event is particularly useful for implementing features like aiming reticles or dragging and dropping elements. The `event.offsetX` and `event.offsetY` properties provide coordinates relative to the padding edge of the target element, which in this case is often the canvas.

An example of capturing mouse clicks and movements on a canvas:

const canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

canvas.addEventListener('mousemove', (event) =>

const rect = canvas.getBoundingClientRect();

const mouseX = event.clientX - rect.left;

const mouseY = event.clientY - rect.top;

console.log(`Mouse at: ($mouseX, $mouseY)`);

);

canvas.addEventListener('click', (event) =>

const rect = canvas.getBoundingClientRect();

const clickX = event.clientX - rect.left;

const clickY = event.clientY - rect.top;

console.log(`Clicked at: ($clickX, $clickY)`);

);

Mapping Input to In-Game Actions

Simply detecting input events is only the first step.

The true power of user input lies in mapping these raw events to specific actions within your game. This involves translating a key press or mouse click into a command that your game logic can understand and execute.

A common and effective strategy for mapping input is to use a data structure, such as an object or a Map, to store the current state of player inputs. This state can then be checked within the game loop to determine what actions the player intends to perform.

For keyboard input, you might maintain a set of keys that are currently being held down. When a `keydown` event occurs, you add the key to the set; when `keyup` occurs, you remove it. The game loop then iterates through this set to determine movement directions or active abilities.

For mouse input, you might track the mouse’s position and whether a button is pressed. This information can be used to:

- Move a player-controlled entity towards the mouse cursor.

- Fire a projectile in the direction of the mouse.

- Select or interact with game objects at the mouse’s click location.

Consider a scenario where you want to move a player character. You can define actions like ‘move_up’, ‘move_down’, ‘move_left’, and ‘move_right’. These actions are then associated with specific keys.

A simplified input mapping strategy:

const keysPressed = ; // Object to store state of pressed keys

document.addEventListener('keydown', (event) =>

keysPressed[event.key] = true;

);

document.addEventListener('keyup', (event) =>

keysPressed[event.key] = false;

);

// Inside the game loop:

function gameLoop()

// Check for movement input

if (keysPressed['ArrowUp'] || keysPressed['w'])

player.y -= player.speed; // Move player up

if (keysPressed['ArrowDown'] || keysPressed['s'])

player.y += player.speed; // Move player down

// ...

other movement checks

Organizing Input Handling within the Game Loop

The game loop is the heart of any interactive game, responsible for updating game state, rendering graphics, and, crucially, processing user input. Integrating input handling into the game loop ensures that player actions are registered and acted upon consistently with the game’s frame rate.

The typical structure involves three main phases within each iteration of the game loop:

- Input Processing: This phase involves checking the current state of player inputs. Instead of directly modifying game state in the event listeners (which can lead to erratic behavior due to timing), you update a dedicated input state variable or array.

- Game State Update: Based on the processed input state, the game’s logic is updated. This includes moving characters, updating scores, checking for collisions, and so on.

- Rendering: Finally, the game world is redrawn to reflect the updated game state.

By separating input capture (event listeners) from input processing (within the game loop), you achieve a more robust and predictable system. The event listeners simply update a shared input state, and the game loop then reads this state to make decisions.

This organized approach ensures that input is handled in a timely manner and consistently with other game logic, leading to a responsive and enjoyable gaming experience. For instance, if a player holds down the ‘jump’ key, the input state will reflect this, and the game loop will continue to register the jump action for as long as the key is held (or until a jump limit is reached), rather than triggering a single jump per key press.

“Decoupling input event listeners from game state updates is key to creating predictable and smooth game controls.”

Game Physics and Collision Detection

Understanding game physics and collision detection is crucial for creating interactive and engaging games. This section will delve into the fundamental concepts of physics that govern game object behavior and explore effective methods for determining when these objects interact. We will then examine how to react to these interactions and manage the states of multiple physics-enabled objects within your game.

Physics in games often simplifies real-world mechanics to achieve desired gameplay. Key concepts like velocity and acceleration are fundamental to making objects move and change their movement over time. Velocity represents the rate of change of an object’s position, essentially its speed and direction. Acceleration, on the other hand, is the rate at which velocity changes, meaning an object speeds up, slows down, or changes direction.

By applying these principles, you can simulate realistic or stylized motion for characters, projectiles, and other game elements.

Velocity and Acceleration in Game Objects

To implement motion, game objects typically possess properties for their velocity and, if applicable, acceleration. Velocity is usually represented as a vector, often with ‘x’ and ‘y’ components for 2D games. This vector dictates how much the object’s position changes in each frame. Acceleration, similarly, is a vector that modifies the velocity over time. For instance, gravity can be simulated by continuously applying a downward acceleration to objects.

A common approach to updating an object’s position based on its velocity is to add the velocity, scaled by the time elapsed since the last frame (delta time), to its current position.

newPosition = currentPosition + velocity

- deltaTime;

Acceleration is applied to the velocity itself:

newVelocity = currentVelocity + acceleration

- deltaTime;

This continuous update loop forms the backbone of dynamic movement in your game.

Collision Detection Algorithms

Collision detection is the process of identifying when two or more game objects occupy the same space. For simple shapes, well-established algorithms exist. These algorithms are computationally efficient and provide the foundation for many game interactions.

Circle-to-Circle Collision Detection

Detecting a collision between two circles is straightforward. It involves calculating the distance between the centers of the two circles and comparing it to the sum of their radii. If the distance is less than or equal to the sum of their radii, a collision has occurred.

Let circle A have center (x1, y1) and radius r1, and circle B have center (x2, y2) and radius r

2. The distance squared between their centers is:

distanceSquared = (x2 - x1)^2 + (y2 - y1)^2;

The sum of their radii squared is:

radiiSumSquared = (r1 + r2)^2;

A collision occurs if:

distanceSquared <= radiiSumSquared;

Calculating with squared values avoids the computationally more expensive square root operation.

Rectangle-to-Rectangle Collision Detection (Axis-Aligned Bounding Boxes – AABB)

For axis-aligned rectangles (rectangles whose sides are parallel to the x and y axes), a common and efficient method is the Separating Axis Theorem (SAT), simplified for AABBs. A collision occurs if the rectangles overlap on both the x and y axes.

Consider two rectangles, Rect A and Rect B.

Rect A: leftA, rightA, topA, bottomA

Rect B: leftB, rightB, topB, bottomB

A collision occurs if all of the following conditions are true:

- Rect A’s right edge is to the right of Rect B’s left edge (

rightA > leftB). - Rect A’s left edge is to the left of Rect B’s right edge (

leftA < rightB). - Rect A’s bottom edge is below Rect B’s top edge (

bottomA > topB). - Rect A’s top edge is above Rect B’s bottom edge (

topA < bottomB).

If any of these conditions are false, the rectangles are not colliding.

Collision Response Mechanisms

Once a collision is detected, a “collision response” is needed to dictate how the game objects should react. This response is highly dependent on the game’s mechanics.

Common collision responses include:

- Stopping Movement: If a player hits a wall, their movement in that direction might be halted.

- Bouncing/Reflection: Projectiles might bounce off surfaces, or characters might be repelled from each other. This often involves reversing or modifying the velocity vector based on the angle of impact.

- Damage/Destruction: In games where collisions can cause harm, one or both objects might lose health or be removed from the game.

- Score/Event Triggering: Collisions can trigger events, such as collecting an item or reaching a goal, leading to score changes or level progression.

For simple physics, like elastic collisions, the response might involve calculating new velocities for both objects such that their kinetic energy is conserved (or a portion of it, for inelastic collisions). For more complex scenarios, game-specific logic dictates the response.

Managing Physics States for Multiple Game Objects

In a game with many objects, each potentially having its own physics properties, efficient management is key. A common pattern is to maintain a list or array of all game objects that are subject to physics simulation.

In each game loop iteration, you would typically:

- Update Physics: Iterate through all physics-enabled objects. For each object, update its velocity based on acceleration (e.g., gravity, player input) and then update its position based on its velocity.

- Detect Collisions: Iterate through pairs of objects and perform collision detection. For performance, this is often optimized using techniques like spatial partitioning (e.g., quadtrees) to only check for collisions between objects that are spatially close.

- Handle Responses: For every detected collision, apply the appropriate collision response logic. This might involve modifying the velocities of the colliding objects, triggering game events, or updating their states.

This structured approach ensures that all physics-driven interactions are processed consistently and efficiently, contributing to a dynamic and believable game world.

Sprites and Image Loading

Sprites are the visual building blocks of most games, representing characters, enemies, items, and other interactive elements. In JavaScript canvas game development, efficiently loading and displaying these images is crucial for creating visually rich and dynamic experiences. This section will guide you through the process of incorporating sprites into your canvas games.

The fundamental step in using images is to load them into your JavaScript code so they can be drawn onto the canvas. JavaScript provides a built-in `Image` object for this purpose, which allows you to create an image element and set its source. Once the image is loaded, you can then render it onto the canvas at any desired position and size.

Loading Images into the Canvas

To load an image, you create a new `Image` object and assign a source URL to its `src` property. It’s essential to handle the `onload` event, which fires when the image has successfully loaded, to ensure you attempt to draw it only after it’s available. This prevents errors that would occur if you tried to draw an image that hasn’t finished loading yet.

Here’s a common pattern for loading an image:

const playerImage = new Image();

playerImage.src = 'path/to/your/player.png';

playerImage.onload = () =>

// Image has loaded, you can now draw it

console.log('Player image loaded successfully!');

;

playerImage.onerror = () =>

// Handle potential errors during loading

console.error('Error loading player image.');

;

Drawing Images (Sprites) on the Canvas

Once an image is loaded, you can draw it onto the canvas using the `drawImage()` method of the 2D rendering context. This method offers several variations, but the most common one for drawing an entire image at a specific location is: `context.drawImage(image, x, y);`. Here, `x` and `y` represent the top-left coordinates where the image will be drawn on the canvas.

To draw the loaded `playerImage` at coordinates (50, 100):

// Assuming 'ctx' is your 2D rendering context and playerImage is loaded

ctx.drawImage(playerImage, 50, 100);

You can also specify the width and height to draw the image at a different scale: `context.drawImage(image, x, y, width, height);`.

Sprite Sheet Animation

Sprite sheets are a technique where multiple frames of animation for a character or object are combined into a single image file. This is highly efficient for game development as it reduces the number of individual image files to load and manage. To animate using a sprite sheet, you need to draw only a specific portion of the larger image onto the canvas for each frame of animation.

The `drawImage()` method has an overload that allows you to specify a source rectangle: `context.drawImage(image, sx, sy, sWidth, sHeight, dx, dy, dWidth, dHeight);`.

- `sx`, `sy`: The top-left coordinates of the sub-rectangle to be cropped from the source image.

- `sWidth`, `sHeight`: The width and height of the sub-rectangle to be cropped.

- `dx`, `dy`: The top-left coordinates where the cropped sub-rectangle will be drawn on the canvas.

- `dWidth`, `dHeight`: The width and height to draw the cropped sub-rectangle on the canvas.

For example, if your sprite sheet has frames that are 32 pixels wide and 32 pixels tall, and you want to draw the 3rd frame (index 2) at position (100, 150), you would calculate the `sx` and `sy` values.

Consider a sprite sheet with frames arranged horizontally:

- Frame 0: `sx = 0

– frameWidth`, `sy = 0` - Frame 1: `sx = 1

– frameWidth`, `sy = 0` - Frame 2: `sx = 2

– frameWidth`, `sy = 0`

If `frameWidth` is 32, then for the 3rd frame (index 2), `sx` would be `2

– 32 = 64`, and `sy` would be `0`. The code to draw this frame would look like:

const frameWidth = 32;

const frameHeight = 32;

const currentFrame = 2; // For the 3rd frame

ctx.drawImage(

spriteSheetImage,

currentFrame

- frameWidth, 0, // sx, sy, sWidth, sHeight

frameWidth, frameHeight,

100, 150, // dx, dy

frameWidth, frameHeight // dWidth, dHeight (optional, if scaling)

);

Organizing Image Assets and Loading States

As your game grows, you’ll likely have many images to manage. It’s good practice to organize these assets and their loading states to prevent clutter and ensure robustness. A common approach is to use an object or a class to hold your images and track their loading progress.

You can create a simple asset manager:

const assetManager =

images: ,

loadedCount: 0,

totalImages: 0,

loadImage: function(name, src)

const img = new Image();

img.onload = () =>

this.loadedCount++;

console.log(`$name loaded.`);

if (this.loadedCount === this.totalImages)

console.log('All assets loaded!');

// Trigger game start or initial rendering

;

img.onerror = () =>

console.error(`Error loading $name from $src`);

;

img.src = src;

this.images[name] = img;

this.totalImages++;

,

getImage: function(name)

return this.images[name];

;

// Example usage:

assetManager.loadImage('player', 'path/to/player.png');

assetManager.loadImage('enemy', 'path/to/enemy.png');

// Later, in your game loop:

// const playerImg = assetManager.getImage('player');

// if (playerImg)

// ctx.drawImage(playerImg, x, y);

//

This `assetManager` keeps track of all images, their source paths, and how many have successfully loaded. This pattern helps in managing dependencies and knowing when it’s safe to start the game or render elements that rely on specific assets.

Structuring Game Code for Scalability

As your JavaScript canvas game grows in complexity, so does the importance of well-structured code. A scalable codebase ensures that adding new features, fixing bugs, and maintaining the game becomes manageable rather than a daunting task. This section will explore key principles and techniques for organizing your game code effectively.

A well-structured game is easier to understand, debug, and extend. By adopting certain design patterns and organizational strategies, you can lay a solid foundation for a game that can evolve over time without becoming a tangled mess.

Object-Oriented Programming for Game Entities

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a powerful paradigm that aligns naturally with game development. It allows us to model real-world or conceptual entities within the game as distinct objects, each with its own properties (data) and behaviors (methods). This encapsulation makes code more modular and easier to manage.

Consider a simple game where you have different types of entities like players, enemies, and projectiles. Using OOP, each of these can be represented as a class.

Example: Structuring Game Entities as Classes

Let’s illustrate this with a basic example. We can define a generic `GameObject` class that forms the base for all entities, and then create specific classes that inherit from it.

class GameObject

constructor(x, y, width, height, color)

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

this.color = color;

draw(context)

context.fillStyle = this.color;

context.fillRect(this.x, this.y, this.width, this.height);

update()

// Basic update logic, can be overridden by subclasses

class Player extends GameObject

constructor(x, y, width, height, color, speed)

super(x, y, width, height, color);

this.speed = speed;

moveLeft()

this.x -= this.speed;

moveRight()

this.x += this.speed;

update()

// Player-specific update logic, e.g., gravity, animations

super.update(); // Call parent update if needed

class Enemy extends GameObject

constructor(x, y, width, height, color, movementPattern)

super(x, y, width, height, color);

this.movementPattern = movementPattern; // e.g., 'horizontal', 'chase'

update()

// Enemy-specific AI and movement logic

if (this.movementPattern === 'horizontal')

this.x += 2; // Example: move right

super.update();

This approach allows us to define common functionalities in the base `GameObject` class, such as drawing and a generic update method, while specific behaviors like movement or AI are handled in the derived classes.

Separating Game Logic from Rendering Concerns

A crucial aspect of scalable game development is the clear separation of concerns. Specifically, distinguishing between the game’s logic (what happens in the game world) and its rendering (how it’s displayed on the canvas) leads to cleaner, more maintainable code.

Game logic typically involves updating game state, handling user input, managing AI, and detecting collisions. Rendering, on the other hand, is solely concerned with drawing the current state of the game onto the canvas. By keeping these separate, you can modify the game’s appearance without affecting its underlying mechanics, and vice-versa.

In practice, this separation often means that your game loop’s update phase modifies the game’s data structures, and the draw phase then uses that data to render the scene.

// Game loop structure example

function gameLoop()

// 1. Update Game State (Logic)

player.update();

enemies.forEach(enemy => enemy.update());

handleCollisions();

// ... other logic updates

// 2. Render Game State (Rendering)

clearCanvas();

player.draw(context);

enemies.forEach(enemy => enemy.draw(context));

// ...

draw other game elements

requestAnimationFrame(gameLoop);

The `update()` methods within your game entities are where the core logic resides. The `draw()` methods are responsible for translating that logic’s outcome into visual elements on the canvas.

Organizing Code into Modules

As your game grows, a single JavaScript file can become unmanageable. JavaScript modules provide a way to break down your code into smaller, self-contained units, each responsible for a specific piece of functionality. This improves readability, maintainability, and reusability.

You can create modules for different aspects of your game, such as:

- Player module

- Enemy module

- Input handler module

- Collision detection module

- Asset loading module

- UI module

Modern JavaScript supports ES Modules natively, allowing you to use `import` and `export` s. For older environments or simpler setups, you might use immediately invoked function expressions (IIFEs) or other module patterns.

Example: Using ES Modules

Imagine you have a `player.js` file and a `game.js` file.

// player.js

export class Player

constructor(x, y)

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

// ... other player properties

move()

// ...

player movement logic

draw(context)

// ... player drawing logic

// game.js

import Player from './player.js';

const canvas = document.getElementById('gameCanvas');

const context = canvas.getContext('2d');

const player = new Player(50, 50);

function gameLoop()

// Update logic

player.move();

// Render logic

context.clearRect(0, 0, canvas.width, canvas.height);

player.draw(context);

requestAnimationFrame(gameLoop);

gameLoop();

This modular approach ensures that each file has a clear purpose, making it easier to find and modify specific parts of your game’s code without affecting unrelated sections.

Advanced Canvas Techniques for Games

As we progress in our game development journey using JavaScript Canvas, mastering advanced techniques will elevate the visual fidelity and interactivity of our games. This section delves into sophisticated methods for rendering complex graphics, manipulating elements dynamically, and enhancing the overall player experience through visual effects and audio.

This chapter focuses on pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with the Canvas API, enabling you to create more engaging and professional-looking games. We will explore techniques that go beyond basic drawing and animation, providing you with the tools to implement visually stunning and responsive game elements.

Drawing Complex Shapes and Paths

Beyond simple rectangles and circles, the Canvas API offers powerful tools for constructing intricate shapes and custom paths. These techniques are essential for creating detailed game assets, unique backgrounds, and visually appealing user interfaces. The `Path2D` object and the `bezierCurveTo`, `quadraticCurveTo`, and `arcTo` methods are key to achieving this complexity.

The `Path2D` object allows for the creation of reusable path definitions. You can draw multiple sub-paths within a single `Path2D` object and then render it multiple times, improving performance. Methods like `moveTo`, `lineTo`, `arc`, `rect`, `arcTo`, `quadraticCurveTo`, and `bezierCurveTo` are used to define the geometry of the path.

- `moveTo(x, y)`: Lifts the “pen” and moves it to a new starting point without drawing a line.

- `lineTo(x, y)`: Draws a straight line from the current point to the specified coordinates.

- `arc(x, y, radius, startAngle, endAngle, anticlockwise)`: Draws a circular or elliptical arc. The angles are in radians.

- `rect(x, y, width, height)`: Draws a rectangle.

- `arcTo(x1, y1, x2, y2, radius)`: Draws an arc connecting the current point to (x2, y2) via a tangent at (x1, y1) with a given radius. This is particularly useful for creating rounded corners.

- `quadraticCurveTo(cpx, cpy, x, y)`: Draws a quadratic Bézier curve from the current point to (x, y), using (cpx, cpy) as the control point.

- `bezierCurveTo(cp1x, cp1y, cp2x, cp2y, x, y)`: Draws a cubic Bézier curve from the current point to (x, y), using (cp1x, cp1y) and (cp2x, cp2y) as control points.

A practical application involves drawing a stylized projectile with a curved trail, or a complex character Artikel. By combining these methods, you can define virtually any shape imaginable within your game.

Transformations for Dynamic Effects

Transformations are fundamental for creating dynamic visual effects and efficiently managing game object rendering. They allow you to manipulate the coordinate system of the canvas, enabling you to translate, rotate, and scale elements without altering their original drawing commands. This is crucial for animating characters, implementing camera movements, and creating parallax scrolling effects.

The Canvas API provides three primary transformation methods: `translate`, `rotate`, and `scale`. It’s important to note that these transformations are cumulative and affect subsequent drawing operations. To manage transformations effectively, especially when dealing with multiple independent objects, the `save()` and `restore()` methods are indispensable.

- `translate(x, y)`: Moves the origin of the canvas coordinate system to the specified (x, y) coordinates. This is useful for positioning elements relative to a new origin.

- `rotate(angle)`: Rotates the canvas coordinate system by the specified angle (in radians) around the current origin. Positive angles rotate clockwise.

- `scale(x, y)`: Scales the coordinate system by the specified factors along the x and y axes. This can be used to make elements larger or smaller.

The `save()` method pushes the current canvas state (including transformations, fill and stroke styles, and clipping regions) onto a stack, while `restore()` pops the last saved state off the stack, reverting the canvas to that previous state. This allows for isolated transformations on different game elements.

For instance, to draw a rotating gear:

- Save the current canvas state.

- Translate to the center of the gear.

- Rotate the canvas by the desired angle.

- Draw the gear (e.g., a circle with teeth).

- Restore the canvas state to remove the rotation and translation.

Implementing Basic Particle Systems

Particle systems are a powerful technique for creating visually rich effects such as explosions, smoke, fire, magic spells, and atmospheric elements. They involve simulating a large number of small, independent entities (particles) that move and evolve over time according to defined rules.

A basic particle system can be implemented by maintaining an array of particle objects. Each particle object typically stores its position, velocity, color, size, and lifespan. In each frame of the game loop, you iterate through the particles, update their properties based on their velocity and other physics, draw them, and remove any particles that have expired.

A conceptual particle object might look like this:

class Particle

constructor(x, y, velocityX, velocityY, color, size, lifespan)

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.velocityX = velocityX;

this.velocityY = velocityY;

this.color = color;

this.size = size;

this.lifespan = lifespan;

this.initialLifespan = lifespan; // To control fadingupdate()

this.x += this.velocityX;

this.y += this.velocityY;

this.lifespan--;

// Optional: Add gravity or other forces

this.velocityY += 0.1;draw(context)

const alpha = this.lifespan / this.initialLifespan;

context.fillStyle = `rgba($this.color.r, $this.color.g, $this.color.b, $alpha)`;

context.beginPath();

context.arc(this.x, this.y, this.size, 0, Math.PI

- 2);

context.fill();isAlive()

return this.lifespan > 0;

To create an explosion effect, you would spawn multiple particles originating from the explosion’s center, each with a random velocity and lifespan. The `update` method would handle movement and decay, while the `draw` method would render each particle, potentially with fading transparency as its lifespan decreases.

Conceptual Approach for Adding Sound

While the Canvas API itself doesn’t directly handle audio, JavaScript provides the Web Audio API and the HTML5 `

The HTML5 `

For more advanced audio features, such as complex sound effects, real-time audio processing, and precise timing, the Web Audio API is the preferred choice. It offers a powerful node-based architecture where audio sources, effects, and destinations can be connected to create intricate audio graphs.

A conceptual approach for integrating sound involves:

- Loading Audio Assets: Preload sound effects and music to avoid delays during gameplay. This can be done by creating `Audio` objects or using the Web Audio API’s `AudioContext` and `BufferSourceNode`.

- Sound Effects Management: Implement a system for playing short sound effects, such as jump sounds, collision sounds, or button clicks. For frequently played sounds, consider reusing `Audio` objects or pooling them to manage resources efficiently.

- Background Music: Manage background music playback, including starting, stopping, fading in/out, and looping.

- Volume Control: Provide options for users to adjust the volume of music and sound effects independently.

- Spatialization (Web Audio API): For 3D games, use the Web Audio API’s `PannerNode` to create a sense of sound coming from different directions relative to the player’s position.

For example, playing a jump sound effect could be as simple as:

const jumpSound = new Audio('sounds/jump.wav');

// ... in your game loop when the jump occurs

jumpSound.play();

When implementing sound, it’s crucial to consider performance, especially on mobile devices. Loading and decoding audio can be resource-intensive, so efficient loading strategies and careful management of audio playback are key to a smooth gaming experience.

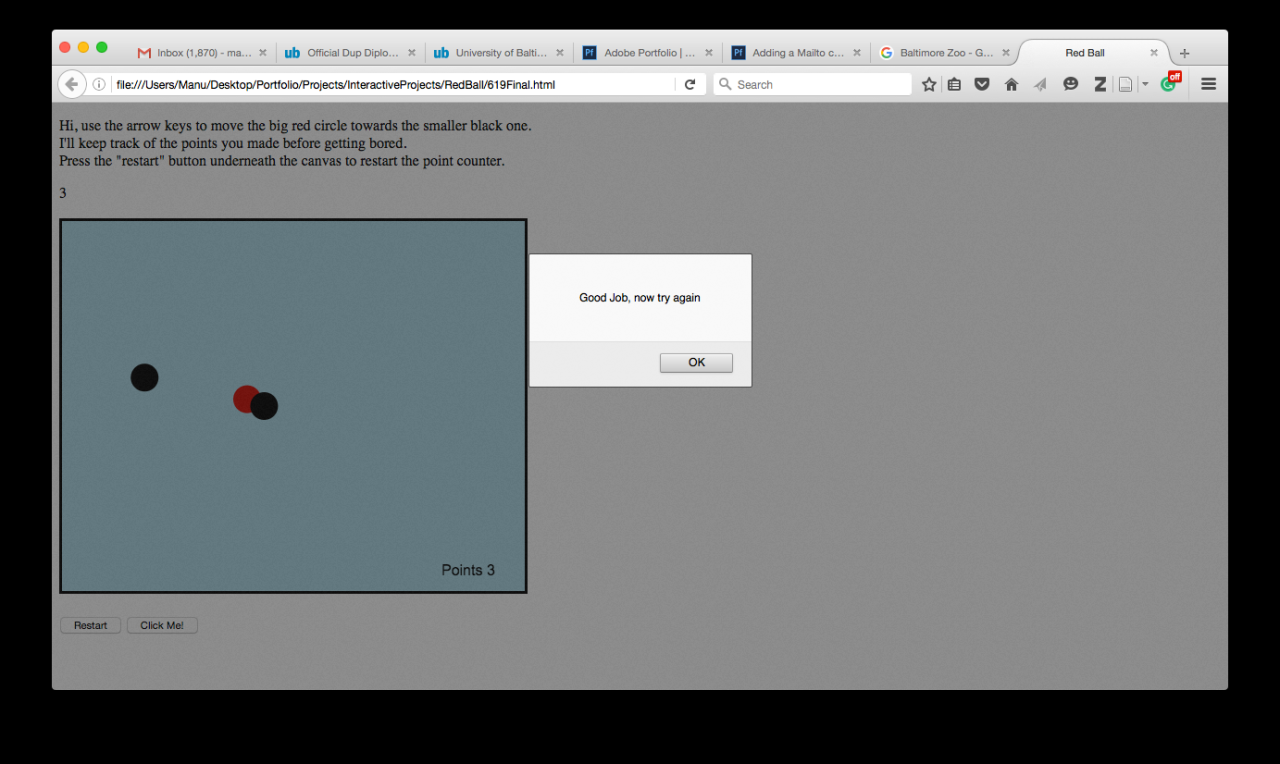

Example Game Mechanics Implementation

Now that we have a solid understanding of the fundamental building blocks of JavaScript Canvas game development, it’s time to bring our game to life by implementing core mechanics. This section will guide you through creating essential gameplay elements, from player control and enemy behavior to scoring and managing game states, all within the Canvas environment.

Implementing effective game mechanics is crucial for engaging gameplay. These mechanics define how the player interacts with the game world, how non-player characters behave, and how progress is tracked and presented. By carefully designing and coding these elements, we can create a fun and compelling gaming experience.

Player Movement System Design

A responsive and intuitive player movement system is fundamental to most games. This involves translating user input into character actions on the canvas. We will design a system that allows for directional movement, often controlled by keyboard arrows or WASD keys.

The core of this system relies on tracking the player’s position and updating it based on input events.

- Input Handling: Event listeners for ‘keydown’ and ‘keyup’ events are essential. These listeners will capture which keys are pressed and released.

- Movement State Tracking: Boolean variables can track the current movement state (e.g., `isMovingUp`, `isMovingLeft`). When a key is pressed, the corresponding state is set to `true`; when released, it’s set to `false`.

- Position Updates: Within the game loop, the player’s x and y coordinates are updated based on the active movement states and a defined movement speed. For instance, if `isMovingUp` is true, the player’s y-coordinate will decrease.

- Boundary Checks: It’s important to prevent the player from moving off-screen. This involves checking the player’s position against the canvas dimensions and limiting movement accordingly.

For example, consider a player moving right:

if (keysPressed[‘ArrowRight’])

player.x += player.speed;

This simple conditional logic, applied within the animation loop, translates a key press into tangible movement on the canvas.

Enemy AI for Basic Movement Patterns

Enemy Artificial Intelligence (AI) dictates how non-player characters behave, adding challenge and dynamism to the game. For basic movement patterns, we can implement predictable yet engaging behaviors.

Simple AI can range from patrolling a fixed path to chasing the player. The key is to make their actions understandable yet challenging for the player to overcome.

- Patrolling: Enemies can move back and forth between two predefined points. This can be achieved by tracking the enemy’s current direction and reversing it when it reaches a boundary.

- Random Movement: Enemies can move in random directions for a short period before changing their path. This adds an element of unpredictability.

- Chasing: A more advanced basic AI involves the enemy moving towards the player’s current position. This requires calculating the vector from the enemy to the player and moving the enemy along that vector.

- Obstacle Avoidance (Basic): For simple scenarios, enemies might stop or change direction if they encounter a static obstacle. More complex avoidance requires pathfinding algorithms, which are beyond basic patterns.

Let’s illustrate a simple patrolling enemy:

function updateEnemy(enemy)

if (enemy.x enemy.patrol.end)

enemy.direction = -1; // Move leftenemy.x += enemy.speed

– enemy.direction;

This function would be called for each enemy within the main game loop.

Scoring System and Displaying on Canvas

A scoring system provides players with a clear objective and a measure of their success. Implementing this involves tracking a score variable and visually representing it on the canvas.

The score should be updated dynamically as the player achieves in-game objectives, such as defeating enemies or collecting items.

- Score Variable: A simple JavaScript variable (e.g., `let score = 0;`) will store the player’s current score.

- Score Updates: This variable is incremented based on game events. For instance, when an enemy is defeated, the score might increase by 100 points.

- Text Rendering: The `CanvasRenderingContext2D` object provides methods to draw text. We’ll use `context.font`, `context.fillStyle`, and `context.fillText()` to display the score.

- Positioning: The score is typically displayed in a prominent location on the canvas, such as the top-left or top-right corner, to be easily visible without obstructing gameplay.

Here’s how you might draw the score:

function drawScore(context, score)

context.font = ’20px Arial’;

context.fillStyle = ‘white’;

context.fillText(‘Score: ‘ + score, 10, 30);

This function would be called in each frame of the game loop to ensure the score is always up-to-date on the canvas.

Game States Management

Managing different game states, such as a start screen, gameplay, and game over, is essential for structuring a complete game. These states control what is displayed and what logic is active at any given time.

Implementing game states helps organize the game’s flow and provides a clear user experience.

- State Variable: A variable, often an enum or a string, tracks the current game state (e.g., `gameState = ‘startScreen’`).

- State-Specific Logic: Conditional statements (e.g., `if (gameState === ‘gameplay’) … `) are used to execute different code blocks based on the current state. This includes drawing different elements, handling different inputs, and running specific game logic.

- State Transitions: Events or conditions trigger transitions between states. For example, pressing “Start” on the start screen transitions the game to the ‘gameplay’ state. Reaching zero lives transitions to the ‘gameOver’ state.

- Rendering Differences: Each state will have its own rendering function or section within the main draw loop to display appropriate visuals. The start screen might show a title and a “Press Enter to Start” message, while the game over screen shows the final score and a “Play Again” option.

A simplified state management structure might look like this:

function gameLoop()

if (gameState === ‘startScreen’)

drawStartScreen();

handleStartScreenInput();

else if (gameState === ‘gameplay’)

updateGame();

drawGame();

handleGameplayInput();

else if (gameState === ‘gameOver’)

drawGameOverScreen();

handleGameOverInput();requestAnimationFrame(gameLoop);

This structure ensures that only the relevant logic and rendering for the current state are active, creating a clean and manageable game flow.

Final Conclusion

As we conclude this in-depth exploration, you are now equipped with the knowledge to bring your game ideas to life using JavaScript and the HTML5 Canvas. From mastering animation loops and user input to implementing physics, handling sprites, and structuring scalable code, this guide has provided a robust foundation. The journey into advanced techniques and concrete game mechanic implementations promises further exciting possibilities, empowering you to create increasingly sophisticated and captivating web games.